Beating the Odds

A Look at Drivers of Investment Performance and Outperformance

This post isn’t meant to be a recipe for beating the market. And, to be honest, I’m not sure anyone can reliably do so (including myself). But I think it’s worth exploring what drives returns in the market and what, broadly, can drive excess returns.

First, let’s define what “The Market” is. For the sake of this post, we’ll use the S&P 500 as our measuring stick, but these ideas are applicable to almost any benchmark.

Can It Be Beat?

What makes the market so tough to beat over the long run is the drastically skewed nature of returns for individual stocks. The concept “Extremistan”, described by Nassim Taleb, where much of the world operates in a winner-takes-all domain. When products and services can be easily distributed to the end user, even a modestly better (or cheaper) product can result in a single company swallowing the entire pie, instigated by the feedback loops of economies of scale and network effects and etc.

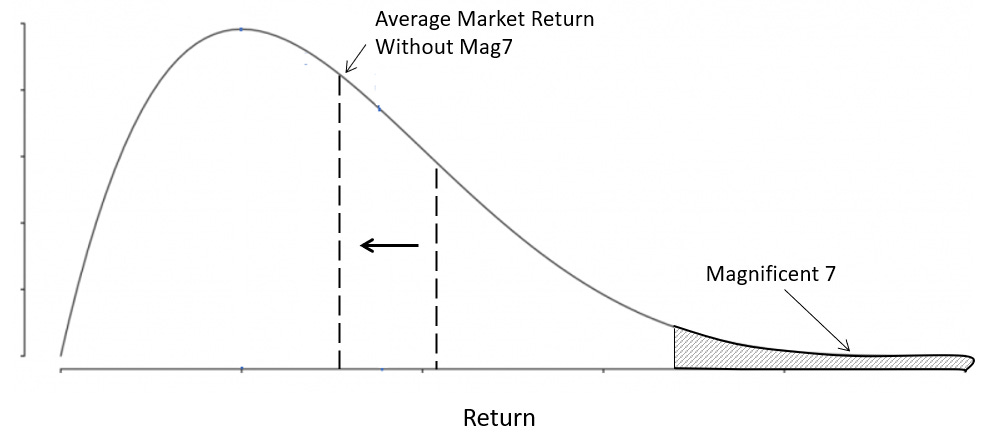

This “winner-takes-all” phenomena leads to a right skewed performance distribution where the overall market returns are carried by the highest compounders (currently led by the “Magnificent 7”, but these highest flyers will change over time).

Just to demonstrate, if you started by putting the full universe of individual securities into a hat, and drew one at random, you’d most likely select a “Performance Dragger.” There’s just more of them. And if you select a handful of stocks at random, even with a few performance leaders, you may still end up underperforming the market if you miss out on the highest flyers.

So can it be beat? The odds are certainly stacked against us right out of the gate. It’ll take some combination of luck and skill to even have a chance.

Drivers of Value

It’s important do understand, at a high level, how a business is valued. I’ll let the reader discover the wonderful world of discounted cash flow analysis and net present value if they so desire, but the components basically fall into the following buckets: future earnings and required rate of return.

Future Earnings

I’m using earnings as a catch-all here, but this is the portion of cash flows that equity holders (or shareholders) are entitled to. These can be distributed directly to investors or can be retained and reinvested by the business.

Required Rate of Return

The required rate of return is simply just that: the return that an investor desires to take on the risk of owning an investment. The riskier the investment, the more return an investor should want for assuming that risk. For stocks, broadly, investors desire a return beyond the risk free rate (typically defined by the yield of the 10 year treasury). The excess desired return is known as the equity risk premium. The equity risk premium can be high or low depending on how risky the investment is. A company with a long track record and stable earnings might demand a lower risk premium than a startup that has yet to even establish revenue. The startup is clearly riskier, so investors will want the potential to earn a higher return for taking on that additional risk.

Finding Fair Value

Fair value (or intrinsic value) is estimated by combining the future earnings estimates and the required rate of return as described below.

Earnings and Fair Value

This relationship works pretty intuitively. Higher earnings means the business is worth more, all things being equal. This relationship is linear: a company that earns double will be worth double. The further into the future the earnings are to be realized the less you care about them, implying that they’re worth less to you than earnings recognized in the short term. Simply stated, you care more about the dollar you will make tomorrow than the dollar you will make ten years from now.

Risk and Fair Value

This one is a little less intuitive, but will hopefully make more sense after the following example.

Consider two casino games: flipping a coin or rolling a dice. The payout for each game, if you win, is $1.00. Now say that I, as the casino manager, set the buy-in amount at $0.50 for each game. Which table will you go to?

The prudent player will head to the coin flipping table because the odds are better while the buy-in and payout are the same (1 in 2 chance for coin flipping vs 1 in 6 for the die rolling). We see that the dice game is higher risk, but without higher returns.

So what would the buy-in need to be at the dice rolling table to make the player interested in switching tables? Intuitively, we’d want to pay less than the coin flip. In fact, to make it a comparable bet, the dice roll buy-in should be priced at $0.166. At this price, an investor would win the same amount as the coin flip, on average.

In these examples, the buy-in represents the fair value for each prospective game. The dice roll is more risky, and lowers the fair value. Notice that the return is higher, paying out 6-to-1 ($1 payout for a $0.166 buy-in) for the dice roll versus 2-to-1 ($1 payout for a $0.50 buy-in) for the coin flip.

The same works for companies. The more risk an investor takes on, the more return they’ll require, and the less they’d be willing to pay for that investment.

Side note: a skilled investor wouldn’t play either of these games as there’s no positive expected value for either game. Per 100 plays, they’d likely walk out of the casino with the same amount of money they walked in with. Only the promise of comped alcohol could make this worthwhile.

How To Beat The Market

We've established what drives valuation in the preceding sections: earnings and risk (as a proxy for required rate of return). Let's explore how we can use these to outperform the market.

More Risk

The easiest way to beat a benchmark is to not even invest into that benchmark at all, but to invest in something riskier instead. If you wanted to beat T-Bills, you could invest in T-Bonds. If you want to beat T-Bonds, you could invest in Investment Grade Corporate Debt. If you want to beat the S&P 500, you could try the Nasdaq Composite or some other high growth / high risk fund.

It’s important to know: higher risk investments offer the potential for, not a guarantee of, higher returns. Howard Marks explains it best in his 2015 memo “Risk Revisited Again”. Figure 3, which I’ve shamelessly taken from Mr. Mark’s memo, illustrates this relationship between risk and return, and how riskier investments have a wider range of possibly outcomes.

Informational Advantage

Any way you slice it, if you want to pick individual securities or even sectors or factors, you’ll need to have some sort of informational edge in order to beat the market. Stop to think for a minute about the possible advantages the average investor might have when it comes to valuation. Can we really expect to outsmart investment banks that have armies of PhD’s and hoards of data at their disposal? Will screening for Current Ratios or Inventory Turnover Cycles or PE ratios really give us an edge? Are we certain that something that passes our screen hasn’t been rightfully left in the dredges for a reason? After all, everyone else in the world has easy access to all of the same information. As individual investors, we have to look where others might not. In fact, it may be the businesses that currently look unattractive that may be the best rocks to turn over.

Aswath Damodaran, Professor of Finance at the Stern School of Business at New York University, advocates for narrative (or story) driven valuation. What this means is that your valuation is subjective, where inputs are largely driven by the qualitative assessment, or an investor’s personal interpretation, of a company’s business model and growth and risk prospects.

So, in order to gain an edge, instead of trying to factor tilt or screen your way to great companies, you should immerse yourself and understand the business at it’s most basic level. Understand the nuts and bolts of how it makes money, and how it turns top level revenue into bottom line income. Not only that, but focus on how to forecast these things into the future. It’s the forecast where the money is made.

You don’t need to have 20/20 vision on the future to be good at this, however. There are many avenues for an investor to find value where most don’t. What about a company that currently isn’t profitable? Most valuation screens will pass right over these as PE ratios will be negative. But if an investor can see a path towards profitability, and can reasonably project the future cash flows, you can find value where other don’t. Or what about a company that is profitable but priced “egregiously” with a high price to earnings multiple? If that company can grow earnings via revenue growth and/or cost cutting, then they can rightfully grow into their current valuation and even beyond.

Informational edges also lend themselves towards catalyst investing (discussed in the next section). Investing in a catalyst, alone, won’t necessarily lead to outperformance over the long run. But if an investor’s career or life experience can give them an edge in estimating the probabilities of an event, or an advantage on predicting the cash flows generated on the other side of said event, he may be able to find some ten cent dice throws paying out a dollar (illustrated later).

Another way to gain an edge in valuation is to simply look where others aren’t. It’s likely not going to be the biggest players with coverage from dozens of analysts where you’re going to find an edge, but smaller, less covered ones.

In a world where AI and “big-data” are taking over the cigar butt side of investing, it’s likely going to be an investor’s qualitative prowess, or imagination, that will lend towards potential long term outperformance.

Catalyst Investing

A catalyst is an event that results in the state change of its subject. For a company, we’re interested in anything that can change the valuation of a companies business, and hope that the stock price recognizes that change. From the fair value discussion above, an event that changes the earnings (both current and future) or the risk profile of the company can result in a discrete change in the value of the company. In fact, even discovering the potential for a catalyst can alter value.

Let’s go back to our dice roll example. The intrinsic value of the game prior to the dice being rolled is $0.166 as we discovered previously. But once the dice is thrown and reveals a number, that value has changed to either $0 in the case of you losing or $1 in the lucky happenstance that you’ve won. The act of the dealer throwing the dice, and the subsequent reveal of the winning number, is the catalyst in this scenario.

Now imagine a dice game parlay, where you must throw 2 dice, one after the other, to win the $1. But you may sell your place at the table at any time. The odds of throwing 2 dice correctly in a row are 1 in 36. For the chance to win $1, a prudent player would want the buy-in to be roughly $0.028 (or $1 × 1/36) because of the long odds. With a buy-in any less than that, a player could play the game many times and expect to win more than they lose (this is known as positive expected return), and it’s favorable to play. If the buy-in is more than $0.028, the opposite happens and it’s unfavorable to play. If you buy a seat at the table for $0.028 and, afterward, the dealer happened to change the buy-in to $0.05, for instance, you’d be best to sell your seat at the table and bank your extra $0.022 since it’s risk free money as no die has been thrown yet.

After the dice is thrown, you were either right or wrong in your guess at selecting the correct number. If you were wrong, you’ve lost and can either ante up again or go home. If you were correct, then congratulations, you’re one step closer to winning the dollar. But here’s the thing, by getting that first dice out of the way, your odds of winning the $1.00 prize have increased. The odds of getting the next dice roll correct is back to 1 in 6, and as we’ve learned previously the fair value for a single dice roll is $0.166. That means, in theory, you should now be able to sell your seat at the table for $0.166, or 6x your original buy-in of $0.028.

This phenomena works for many areas in business and investing: Pharma companies that are progressing through clinical trials (Phases 1 thru 3), aviation companies that are trying to get FAA Type Certificate for an aircraft, a startup gaining it’s first customer. Each have their own risks and probabilities. Clearing a milestone is a risk-off catalyst, where a discrete change in valuation can be measured. In business news, you might hear the phrase “rerated”, meaning the valuation or price-target has changed to reflect the new information.

Let’s consider the pharma company. The overall success rate of passing all three phases and the regulatory review process for approving a new drug is just under 10%[1]. If you were to bet on a particular drug passing all 3 phases and reaching end consumers, you’d first need to calculate the intrinsic value of that drug (assuming it has reached the market), and then discount it for the likelihood of it getting to market. If the drug you were betting on had a worth of $1 billion if it were to actually clear all the FDA hurdles; you, the investor, would only be interested in investing in it, prior to initial Phase I trials, in the ballpark of $100 million (or 10% of the final value).

Once passing Phase 1, the odds of making it through to regulatory approval are now 15%[1]. The valuation heading into Phase 2 would become $150 million (a cool 50% increase over your initial investment).

The pharma example is one where the change in risk is discrete, similar to the dice throw. There are also instances where the change in risk can be gradual. A company or sector or general market can gradually, over the course of months or years, see changes in it’s risk profile. Something that becomes more risky over time will see it’s returns suppressed below what they otherwise would have earned, while something that becomes less risky will see it’s returns boosted. This phenomenon may partially explain the rise in PE valuations for U.S. stocks. If U.S. stocks are perceived as less risky now than they were in the past, their valuation will be discounted less than at riskier points in history. This means that investors will pay more for the same stream of cashflows than they otherwise would have. But it also means that the return expectations for the future will have also decreased: lower risk mean lower returns.

There are also other types of catalysts as well. A company announcing a new business segment will affect future cash flows. Entrants of new competitors to a market segment will negatively affect cash flows for the existing players by way of both potentially reduced sales volume and tightening profit margins. Changes to the tax code affect earnings. Likewise, changes in interest rates can have similar affects on cash flows (in the case that a company owes debt) as well as to the discounting mechanism used in your required rate of return. The list is endless.

Note that in almost all cases, the catalyst is the announcement of change, not the implementation itself. This is why you’ll see a stock jump on news, but may be relatively flat when the change actually occurs.

As alluded to previously, chasing catalysts won’t necessarily help you beat the market (unless you’re relying on small samples and luck). Take our dice roll example. For every one hundred rolls (on a single roll game), the player would pay $16 for the privilege of playing those one hundred games, and expect to win 16 times for a total winnings of $16, leaving the table with a net profit of $0. The prudent player will only buy in when expected value ($0.16 per play) exceeds the buy-in. If the buy-in were $0.10 for instance, that same player would spend $10 buying in and expect to win $16 for a net profit of $6 (or 60% on his initial investment). It is necessary for an investor to both know how to value companies and have an informational edge to recognize and act on opportunities such as the $0.10 dice throw.

Also note that in the examples above, we should be discounting for time as well; especially in the pharma scenario where drug approvals can take several years. I’ve excluded that component for the sake of simplicity.

Pick Investments With Right Tails

One attractive investment quality is asymmetry, where there’s more upside than downside. This can look like many things depending on the type of investment.

For a startup, the risk of the business shutting it’s doors may be quite high leaving the downside potential of a 100% loss. But in the case of success, the upside can be virtually unlimited. This binary condition where failure = 0, success = 1 is similar to our dice throw catalyst example. And as with the dice throw, weighing probabilities is going to be a large component for valuing this type of business. For example, if a particular startup would fail 90 times out of 100, an investor would probably want to see a 20x upside potential in the case that it does succeed.

Another type of asymmetric opportunity to look for is when a company is primarily valued for it’s core business model while it has other irons in the fire that aren’t accounted for yet. Think of Amazon when their valuation only accounted for their retail business or Nvidia when they were just a gaming company. In both scenarios, they broke into other markets that vastly expanded their profit potential.

In the latter case, it’s helpful to be able to value the potential, but not needed since you’re buying Amazon for it’s core business and getting the upside potential for free.

Conclusion

This isn’t meant to be an exhaustive list, but rather a few ideas on where you could start your search for the future winners. It’s really hard to beat the market, but I think these ideas are worth considering even if you just want to generally understand how market and company valuations work.

Citations

[1] Mullard, A. Parsing clinical success rates. Nat Rev Drug Discov 15, 447 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2016.136