Dilution: When Price Affects Value

Summary

The following observations can be made from this exercise:

The Direct Method of valuation adjusts cash flows by subtracting non-cash expenses (such as Stock Based Compensation) from CFO (cash flows from operations), and takes no action to account for dilution, directly.

The Share Tracking Method measures the impact of dilution across time by tracking the cash flows that are owed to a single share - more dilution means less future cash flows going to each share.

The Direct Method and Share Tracking Methods are equivalent only when the current share price is equal to fair value.

If dilution is expected to occur at prices that differ wildly from the Direct Method, the Share Tracking Method is required to accurately assess fair value for the company.

To best apply the Share Tracking Method (when price does not equal fair value), the investor benefits from having some knowledge or intuition of what the “path” to fair value may look like.

Introduction

Fair Value is moving target.

Think about the prospect of earning $1 two years from today. If discounted at 10%, the “fair value” of that arrangement would be worth 82¢ today. After a year passes, the arrangement would grow to 91¢ simply because we’re that much closer to the redemption of the $1. And of course, after another year passes, and we’ve reached pay-day, the arrangement is worth the full $1.

This particular mechanism shows up very well when evaluating pre-revenue companies. As time passes, we move toward actual cash flows (similar to the $1 arrangement above), and we’d expect the value of our investment to grow to reflect that.

So imagine my confusion when I was updating my Quantumscape valuation (Original Analysis Here) and my fair value price target actually went down.

Why would that be? We’re a year closer to cash flows. Shouldn’t our fair value target grow in a similar manner as the $1 arrangement, above?

The answer is obviously dilution. I’ve written previously on the topic of dilution - Dilution: When Less is More. In that post, I quoted Aswath Damodaran’s lectures on the topic where he describes that the appropriate approach for accounting for dilution is to simply expense it in terms of dollars - we’ll refer to this as the “Direct Method”.

But. There’s an implicit assumption inside this method that dilution occurs at fair value. I touched on this in the original dilution article, and I suspected there would be an impact when performing my Quantumscape valuation, but always envisioned the impact being pretty minimal. And while the impairment made to my QS valuation wasn’t massive, it was large enough to warrant actually building dilution directly into my valuation model. This post will cover when it’s necessary and how to account for dilution when price deviates from fair value.

Direct Method

First, I’ll cover an example of simply accounting for dilution as an expense as Damodaran does in his notes.

Let’s consider a fictitious widget producing company, WIDG.

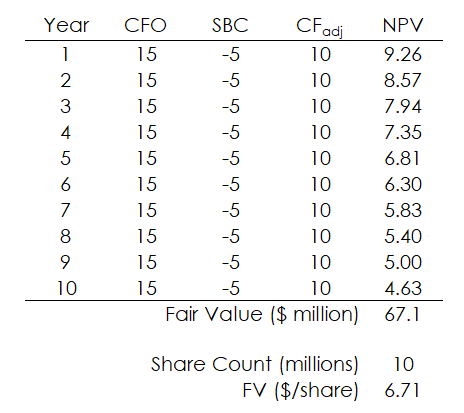

Figure 1 shows that when we adjust cash flows to include stock based compensation, we get a fair value of $67.1 million for the firm - $6.71 share price.

Share Tracking

To track dilution directly, the best way is to think like a share owner. If I buy one share of WIDG, what is my claim to the cash flows produced in the future?

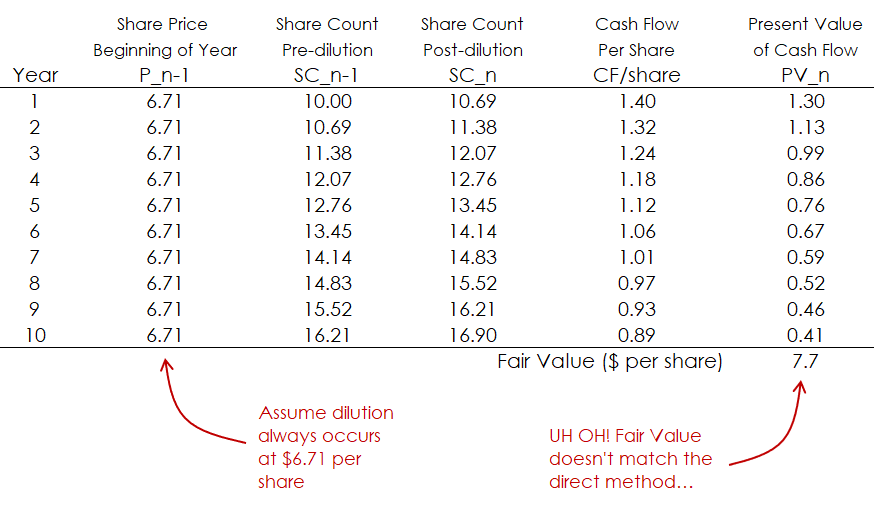

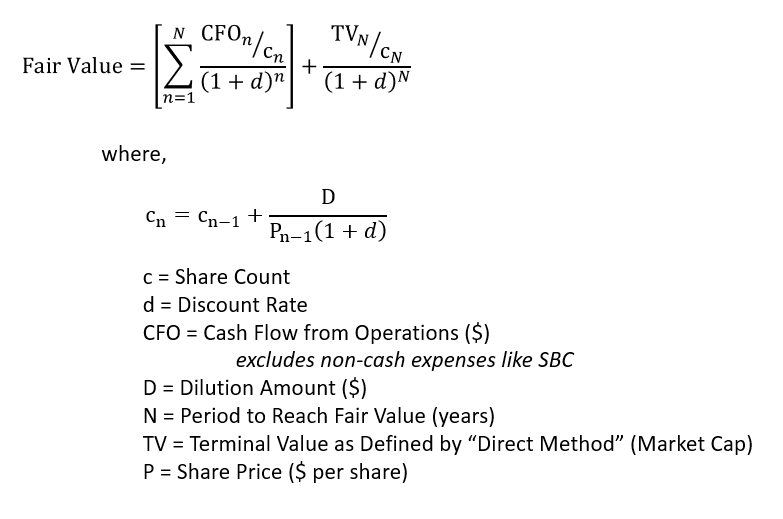

In Figure 2, we see that our claim to the cash flows from operations (CFO) would be $1.40 for our single share after dilution in the first year; and then less for each proceeding year after that. This is what defines dilution, after all.

But right away, we can see some discrepancies. First, our calculated fair value per share comes in 15% higher than the direct method. If the two methods are to be equivalent, their fair value calculations should match.

Second, we can’t assume a steady $6.71 share price for every year. The share price should change over time since a) we’re getting diluted and the share counts are changing every year and b) the cash flow runway is shrinking with each passing year.

In fact, the sum of present values for years n “and-on” should equal the share price at the start of year n (after correcting for time). That sounds confusing, but see below.

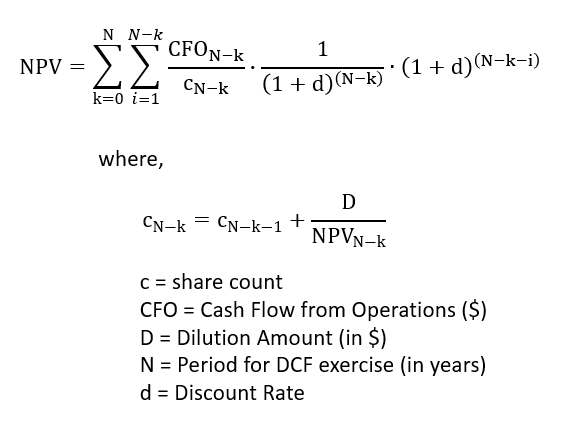

This is starting to get messy, and we’re not done yet. We’re also starting to see a recursive loop. Fair value share price is dependent on share counts, and share counts are dependent on dilutive price, and dilutive price is assumed to be equal to fair value. In addition, fair value for each year is dependent on the the present value of cash flows for each following year (as shown in Figure 3). So it’s clear that each year’s cash flow (per share) and valuation isn’t independent of every other year.

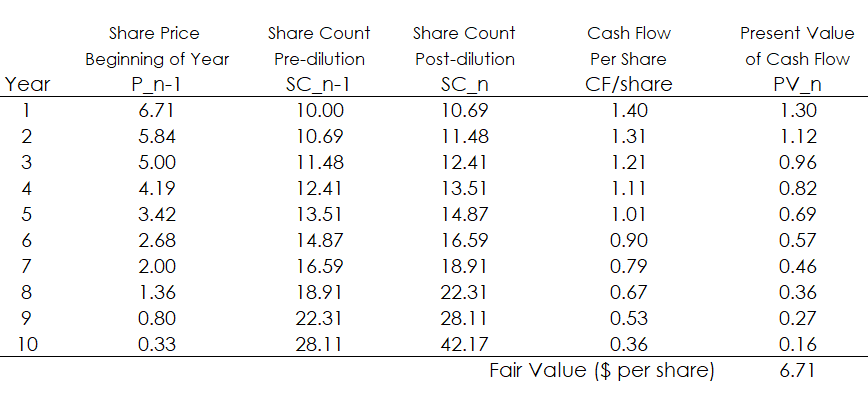

Luckily, using excel’s goalseek function, we can apply these boundary conditions in Figure 3, and solve for fair value.

And voila. Our fair value matches the Direct Method.

It’s hard to gain any real information from this particular exercise. The plummeting share price and exponential growth in share count is mostly a function of capping the company’s life to 10 years.

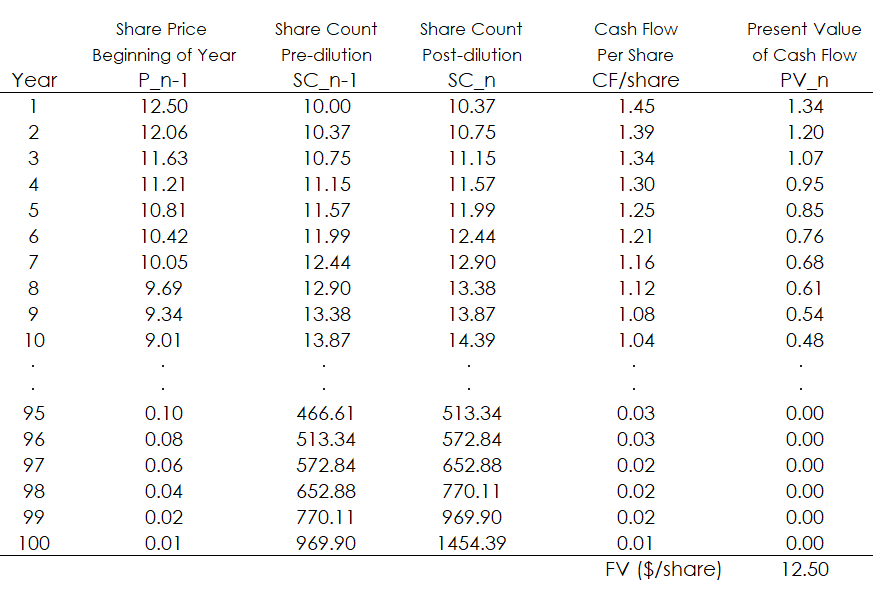

Looking at a more perpetual company, going out to 100 years, we see the following:

First, note that the fair value summation is equal to the price at t=0 (P_n-1 for year 1). This is the defining boundary condition for this method. Next, the $12.50 valuation tracks what we’d expect from the Direct Method.

So the Direct Method is a valid procedure for calculating fair value…when the stock is trading at fair value.

Also note that share price falls as share counts rise. This is expected since we’re assuming no growth in cash flows. The falling share price isn’t a bad thing, though. Investors will still expect 8% IRR on their investment (this assumes that all operating cash flows are paid out to investors).

And just for the sake of completion, here is the defining equation and boundary condition.

Okay, this is all great, but we don’t really need a complex recursive solution for finding fair value when the simple Direct Method works just fine.

But, the core tenet of the Direct Method is that dilution occurs at fair value. What happens when a stock isn’t trading at fair value?

Dilution While “Under Valued”

Thinking about this abstractly, what would we expect to happen when the current share price is below the Direct Method’s estimate for fair value?

If we consider dilution to be a steady dollar amount (most share based compensation has a dollar target & most capital projects are also priced in dollars, not shares), then, if the price-per-share is lower, more shares are issued to cover the needs of the business. And, as more shares are issued, that pulls down the cash flows per share in subsequent years, which lowers the present value for each existing share.

So we see another feedback loop where price drives share dilution, which in turn drives fair value. Again, I’ll provide the equation, but we’ll walk through it:

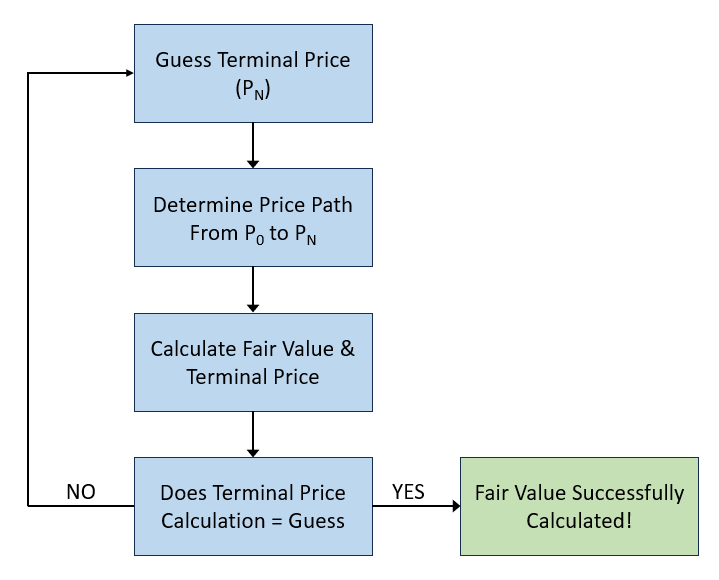

Since Fair Value is dependent on share counts, and share counts are dependent on price, we need to make some assumptions about the path of the stock price.

First, we typically already know what today’s price is as public companies are marked by the second. Next, we need to make some assumptions about the price path to fair value. This will be very much company specific.

If we’re valuing Proctor and Gamble, we might assume that the market will correctly mark the company within the next year or so.

Conversely, if we’re considering a very risky pre-revenue company that is waiting on some catalyst (or series of catalysts) to mark in the price of a previously very uncertain future, then the timing of the price movement will look very different.

The poster child for this type of scenario (catalyst driven valuation) would be my Quantumscape Bull Thesis. Here, the price differs, wildly, from what would be considered fair value for that scenario. However, using the Direct Method (which is what I did use for my initial analysis) has the inherent assumption that dilution is occurring much higher than the current share price.

The procedure is as follows:

Let’s look back at our WIDG example. Let’s say that the stock is currently priced at $2 per share. We’ll make the following assumptions about the path to fair value:

Today’s Price = $2 per share

It’ll take 5 years to reach fair value

Each year will have an equal percentage gain in price - roughly equal steps to fair value.

From here, we can calculate fair value.

Note that Terminal Price equals P_6 (both in bold) - this is the boundary condition that must be satisfied.

We see that the fair value for the stock is $8.95…about 30% less than the direct method fair value of $12.50. In cases such as this, a lower share price actually pulls down the fair value of the company.

The follow-on for this is that a bump in share price actually lifts the value of the company.

Note that in this particular case, the current price of the stock is 85% below the Direct Method fair value. This could imply that there may be a wide price range such that the Direct Method could be considered “close enough”. We can’t, yet, make any sweeping judgements - or define any “rules of thumb” - from this simple exercise, alone. More work would be needed as the WIDG example assumed no growth in earnings which could greatly affect the impact of pricing on fair value.

Summary

The following observations can be made from this exercise:

The Direct Method adjusts cash flows by subtracting non-cash expenses (such as Stock Based Compensation) directly from CFO (cash flows from operations), and takes no action to explicitly account for dilution.

The Share Tracking Method measures the impact of dilution across time by tracking the cash flows that are owed to a single share - more dilution means less future cash flows going to each share.

The Direct Method and Share Tracking Methods are equivalent only when the current share price is equal to fair value.

If dilution is expected to occur at prices that differ wildly from the Direct Method, the Share Tracking Method is required to accurately assess fair value for the company.

To best apply the Share Tracking Method, when price does not equal fair value, the investor benefits from having some knowledge of what the “path” to fair value may look like.