This is a topic that I’ve talked around pretty frequently in this forum, but I feel that it really deserves it’s own post because I plan on referring back to it frequently in the future.

I covered this topic briefly in Beating the Odds, but I really want to expand on it because much of my trading philosophy revolves around determining the probabilities and timing of an event occurring. Notice that I said “trading”. I define myself as an investor, one that buys businesses with the intention on holding for the long term. But I do think there are occasional opportunities where we can exploit the proverbial $10 dice throw (more on that later).

But first, let’s define what a catalyst is in the context of investing. A catalyst is an event that results in material change for a business and it’s valuation. Often, investors are aware of this event, and the stock price typically reflects its anticipated impact. Think of the pharma company in my post, Beating the Odds. Investors sole attention for a new drug will be on it’s progress through the different phases of FDA trials. Every time it passes a trial, the drug is de-risked slightly, and the stock price should go up to reflect that. If the drug fails a trial, the value of that drug effectively goes to zero. If that’s the only drug in the pipeline, the stock effectively goes to zero.

Notice, that in the last example, the value either goes up or goes down after the event. This, again, is because the valuation reflects the “known” nature of the event. There are often cases where the event is a surprise. Think of the 3M earplug lawsuit. Or looking out more broadly, the GFC and Covid crashes. In these cases, the stock (or overall market) was priced fairly, assuming earnings and cash flows would continue growing, blissfully, into the future. When 3M, and subsequently, their investors, were informed of the potential lawsuit with a claim of 10’s of billions of dollars (over 10% of their market cap at the time), the stock tanked because their valuation needed to reflect the potential for the adverse effects to their cash flows and balance sheet.

More broadly, when the housing market began to collapse leading to bank failures and an economic crisis, or covid shut the economy down and lead to governments around the world scrambling; future cash flow projections plummeted and uncertainty spiked, dropping the market with swift regard. This is largely why there’s a risk premium to begin with. If we knew of every trapdoor in the markets, then we would arbitrage our way to the risk-free rate of return. See What Is Risk for further reading.

Not all “surprise” catalysts are bad, however. Nvidia, originally a budding player in the gaming industry, was priced in the early 2010’s as simply a value add to gamers. They offered better graphics capabilities, and their niche loved them. But soon their chips were bought up in droves as their gpu’s were perfect compliments for crypto mining. Anyone remember this couple?

And now AI. Every time Nvidia was able to expand into a new market, their cash flow projections grew, their income streams diversified, and now they’re the second or third largest company in the world (depending on the day). In both of these cases, the expansion to new markets acted as a catalyst.

The $10 Dice Throw

I’ve talked about this in previous posts, but I’ll quickly rehash it here because it’s a very important concept to grasp for event-driven valuation.

Imagine you’re betting on a single dice throw. For a $1 bet, a fair payout will be $6. This is because, as the bettor, you have a 1 in 6 chance of winning. With a $6 payout, neither you, nor the dealer are expected to come out ahead in the long run. This means any expected value has been effectively arbitraged away.

But, there may be times where you stumble upon situations where the dealer doesn’t know the true value of the bet they’re offering. If the dealer were to offer you a $10 payout for a $1 bet, you’d sit and rake in wins all day.

Just like the dealer in the example above, in an inefficient market, you can sometimes stumble upon situations where the market knows how to properly price neither the value nor the probabilities of an event. This is the $10 dice throw.

Pricing an Event

In Beating the Odds, I explored the valuation of a hypothetical Pharmaceutical company going through FDA trials. I won’t cover the math here, but you can refer back to Beating the Odds for a little more thorough explanation..

But big picture; if we wanted to try to value this company at any given time, we first need to figure out what the value would be in the event that they succeed all the way to commercial scale. After which, we would adjust the valuation at each discrete time of the different phases of the FDA process. The resulting valuation plot is shown in Figure 1.

Note that the size of the “jumps” will depend on the probabilities passing each phase. The lower the odds, the bigger the jump. You can start to see the appeal for catalyst investing - there are potential for big gains in short periods of time. Like the dice throw example, this style of investing is highly speculative, bordering on outright gambling. It’s not recommended for most investors.

In a perfect world, an efficient market would price the stock as follows:

In Figure 2, the market does a effective job of assessing both the value and probabilities for the company’s events. This is effectively a $6 dice throw. There’s no positive expected value to be had on either side of the trade. You can experience big wins when things go your way, but on average, you’d expect roughly break-even returns.

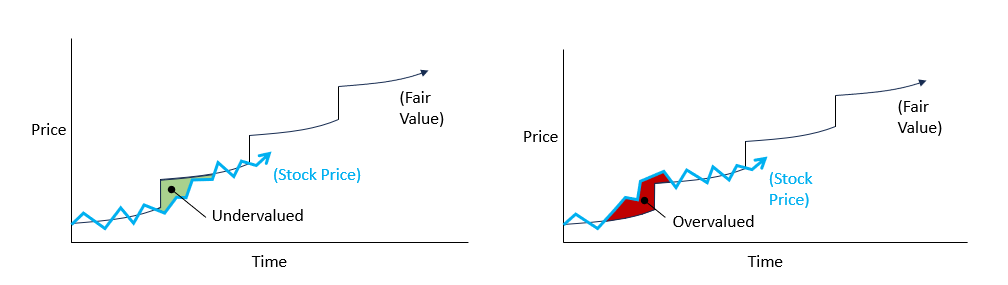

Where things start to get interesting is when the market does a poor job of assessing either the valuation of the company or the probabilities of passing a milestone. See Figure 3.

In the left image, the market does a poor job of initially assessing the valuation after clearing Phase I. In this example, the long term investor could buy the stock and expect a positive return. Buying in the green region would be the coveted $10 dice throw - where the player would be taking advantage of the dealers ignorance.

In the right image, the market front runs the potential of passing Phase I trials. Note that in this example that there are points where the stock is classified as overvalued that would still have positive returns in the event that the drug passes Phase I trials. But the value proposition is a poor one because the upside potential doesn’t outweigh the downside. And given enough plays, an investor would expect poor results on average. This would be classified as a $3 dice throw - where the dealer has the advantage and the player is a sucker.

It is imperative for the investor to know how to calculate both the probabilities of the event and the value of the company. There will be no roadmap drawn showing you the fair value of the company at different stages.

Trading the Event

There are many different strategies for trading around a catalyst theme, and different things will work depending on the type of catalyst we’re thinking about. I’ll discuss generalities, here, because there won’t be a one size fits all in real life. There are certain advantages and pitfalls for each of these techniques. The following isn’t advice, and isn’t exhaustive. See disclaimer below.

Obviously, the easiest way to “play” a catalyst is to simply buy or short the stock. This is a reasonable proposition if you want to hold the position for the long term or you don’t know the exact date of a catalyst.

You can also use options to make the trade more one-sided. You can generate similar returns while making a much smaller bet than you otherwise would have by buying the stock, outright. The downside for options positions is that the timing is very important, not just for the catalyst, but also for the market to recognize and fairly price it. Even if you knew the exact date of an announcement, the market may be slow to reprice the stock. In that event, you’ll be wrong even though you were right.

You can also use options to hedge your position. In our pharmaceutical example, you could purchase the stock ahead of the Phase I announcement and purchase a put option at the same time. In this scenario, your upside is unlimited, while your downside is limited depending on the strike and premium of the option you purchased.

Unfortunately, it’s never that easy. In most cases, for events that are common knowledge - like a Phase I trial release - the options premiums will likely be high enough to remove their hedging effectiveness. In this case, the options pricing is efficient.

In fact, at the time of this writing, there’s a certain Meme-stock that, although I’m nearly certain will go down in the near term, has it’s options priced such that purchasing a put option would require the price of the underlying stock to decline by nearly 50% before breaking even. Although my intuition is very likely correct about the stock price falling, I can’t say I’m interested in taking that bet. What’s funny is, I have no interest in taking the other side of the bet either as I wouldn’t be surprised in the slightest if it did happen to fall by more than 50%. This is the definition of “efficiency”.

So again, you’ll need to find situations where either the market isn’t privy to an upcoming event or has mispriced it in some way. And like with any speculative investment, a generous margin of safety is highly recommended.

Disclaimer

The information provided here is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice. We do not provide personalized investment recommendations or endorse any specific investment products. Investing involves risk, including the potential loss of principal. You should consult with a qualified financial advisor or investment professional before making any investment decisions. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Our content is based on sources believed to be reliable, but we do not guarantee its accuracy, completeness, or timeliness. We are not liable for any errors or omissions in the content or for any losses, damages, or injuries arising from its use.