You may have come across someone that says something to the effect of “just put a couple thousand dollars in just in case it moons”. This usually applies to things like Bitcoin or some other highly speculative asset.

I find myself doing the math on that and coming to the conclusion that even if Bitcoin rose to a million, the prospect of turning $2k into $20k - on a bet that I have no conviction in, have no way of truly valuing, and over an undefined timeframe - just doesn’t interest me in the slightest.

But that got me thinking. How much should I be allocating to an idea, in general, and what considerations should I take into account to actually make the exercise of self-managing worth it?

As a general rule of thumb, I’ve always felt that if I wasn’t comfortable allocating at least 5% to any given asset class, it’s probably not worth allocating anything to it at all. Is it really worth putting just 1% of your portfolio into emerging markets, for instance? EM would have to do INCREDIBLY well to move the needle on your long-term wealth.

But I think this question goes much deeper. Growth potential, and potential impact on long term wealth, is just one aspect of deciding an allocation size. I’ll cover some thoughts below.

Tangible Benefits

In general, I think it’s reasonable to expect some tangible benefit for adding a new asset (or asset class) to your portfolio. For instance, I wouldn’t spend a lot of mental capital on deciding whether I should split my US allocation into VTI (Total Stock Market Index - US) and VOO (S&P 500 index). Both will have about the same returns, and both are highly correlated to each other. If adding an asset to your portfolio isn’t expected to yield higher returns or improve volatility, then why add it to your portfolio at all?

Right away, we can narrow down the two primary considerations as excess returns and diversification.

Diversification is primarily used to “smooth the ride” of investing, and largely results in some drag over the highest expected return asset in the portfolio. Bonds have lower expected returns than stocks, for instance. But, there can be some value in getting to “basically” the same place on a much smoother path.

But just like anything else, adding a 1% position of bonds to an all-stock portfolio doesn’t move the needle on diversification benefits.

Finding the proper weights for asset classes in your portfolio, from a diversification standpoint, is an exercise of estimating the the volatilities of the assets in your portfolio as well as the correlation between those assets. Here's a quick overview of what that process might look like.

The perfect portfolio would consist of asset classes that all have the same expected returns and are highly uncorrelated with one another. This portfolio would offer smooth returns all the way to the finish line.

But I’m not here to talk about diversification. I only mention it because it is very important for portfolio construction. I’m here to talk about about how we should think about adding the marginal position (or next position) to an otherwise well-constructed portfolio.

Excess Returns

Before talking about excess returns, we can start off by inversing the problem: At what point is portfolio drag is too high?

That answer is pretty easy, and corresponds to general the consensus around expense ratios for ETFs and mutual funds. The investment community repeatedly shuns actively managed funds that charge 100 basis points or higher. If this is the threshold where returns start to matter on the downside, we can also use this as our starting point for the level of excess returns that will have a meaningful impact to the upside.

Put another way, is it worth all the effort of asset research and selection just to beat the market by 10 basis points? $100k will grow to $259k in ten years at a 10% CAGR. A 10 basis point edge would instead grow that initial investment to a ‘whopping’ $262k - 1% cumulative outperformance over that same 10 year timeframe…doesn’t seem worth it to me.

In contrast, an asset that provides 100 basis points in excess returns (11% CAGR) would grow $283k in ten years - 9.6% cumulative outperformance. Even that seems a little light, but that level of compounding would be quite meaningful over very long time horizons.

Note that there’s nothing magical about 100 basis points. It just seems like a decent, round number, as a starting point. You can make it higher or lower if you’d like.

So how can we achieve these levels of excess returns, at the portfolio level, when adding a new position to an existing portfolio? There’s really only two variables:

Expected excess return for the new asset, and

Position Sizing

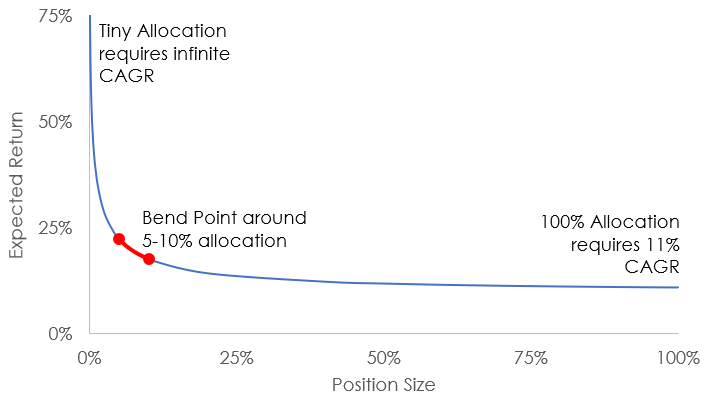

If your portfolio, invested in “the market”, has an expected return of 10%1, and you wish to put in effort to add 100 bp of excess return to that level (increasing your portfolio return to 11% CAGR), you can either purchase a small amount of something with explosive expected returns or a large amount with marginally more expected returns than the market.

More plainly, if you were to purchase an asset that has 11% expected returns, you’d need to put your entire portfolio into that asset to actually see 100 bp of outperformance. (Naturally, you lose diversification benefits by putting all of your eggs in one basket.)

Now consider that you only wanted to allocate 5% of your net holdings to a new asset class (leaving the other 95% in “the market” still earning 10% returns). If we want our total portfolio to grow at 11% CAGR (100 basis points over the market), we can solve for the level of outperformance required from the new asset class to achieve this.

And the answer is 22% returns are required for a 5% allocation to lift total portfolio returns from 10% to 11%.

We can perform this exercise with varying levels of concentration, and we can see the relationship between position size & required level of returns to turn an otherwise 10% compounding portfolio into an 11% compounding portfolio. See Figure 1.

From this plot, we can see some interesting relationships. Right off the bat, some common wisdom shines right through; anything less than a 5% allocation will have a minimal impact on portfolio returns unless they offer truly explosive levels of compounding. Throwing a few hundred bucks at bitcoin probably isn’t going to make a difference to your overall wealth in the long run.

In addition, required excess return flatlines as position size grows. There’s diminishing returns to growing the allocation beyond a certain point. And you begin losing diversification benefits as you move beyond the 10% allocation bend point, anyways.

Conviction

The third major factor (after diversification and compounding math) is your conviction in a position.

Naturally, the higher your conviction, the more you can allocate to an idea. See Figure 2.

This is more qualitative than anything.

There is nuance, here, in terms of what ‘conviction’ can mean.

First, there’s conviction of a defined outcome (Type I Conviction). An example would be buying a company’s stock where you are highly certain of a particular outcome - whether it’s future growth prospects or the outcome of a discrete event (such as a drug company passing phase III trials) or something else. This level of certainty can come from industry level experience, insider knowledge, deep research, etc.

The second is conviction in the universe of potential outcomes (Type II Conviction). This has to do with known-unknowns and unknown-unknowns. If you know that a dice throw has a one in six chance of landing on a number, you can bet with high conviction. You know both the odds and the payout. Alternatively, if you’re not even sure how many sides the dice has, you can’t reasonably determine the probabilities of being right nor the amount you stand to win. And if that’s the case, how could you possibly know the right amount to bet?

If you follow my other letter, you’ll know that I’ve attempted to analyze Quantumscape. I use probabilities frequently in my valuation. Now, I don’t have any earthly idea how likely they are to succeed (lacking Type I Conviction). But, I do think I have a decent handle on how many sides the “dice” have. And with that, my conviction comes from watching the business and tracking the milestones needed for the company to turn profitable.

And from there, I feel that I can use some other method - such as the Kelly Criterion - to help determine the proper position size.

Conviction is also important from a behavioral standpoint. Having some level of mental fortitude helps hold onto positions even when price turns against you. One tell that can help you decide if you have conviction is if stock price movement affects your feelings about the stock in your portfolio. If so, you probably don’t have much conviction, and you should probably at least scale back your holding - if not, exit entirely depending on whether you violate Figure 1 - i.e., if scaling back makes the position too small to meaningful impact overall returns, why hold it at all?

When it comes to price, you should think of yourself as a quarterback - keep your eyes upfield and focus on business milestones and your forecast for the business. Price should really only factor in when you’re comparing against your personal assessment of value for the business.

Expected Returns vs Possible Returns

Circling back to expected returns, it’s worth exploring the difference between expected returns and potential returns.

Expected returns are the outcome that weigh all the potential outcomes. If a typical dice throw pays out 6:1 (a fair bet), your expected returns are 0% - if you play the game many times over the long run, neither you nor the dealer will make any money.

But, if you play the game once, you have a small chance of catching a 6-bagger. This would be one "potential outcome”. Keep in mind that you’re overwhelmingly more likely to lose your entire investment.

Therefore, when given the choice between two assets that have similar expected returns, some deference should be given to the one that has the wider range of outcomes - especially if the distribution is asymmetric to the upside.

I previously explored this in The Place For Luck in Your Portfolio.

In addition, you can use the upside scenario when determining the optimal position size. If the expected excess return is only 100 basis points, but there’s a small chance that it compounds much higher, you can probably hold a smaller allocation than what would otherwise be considered optimal as defined in Figure 1.

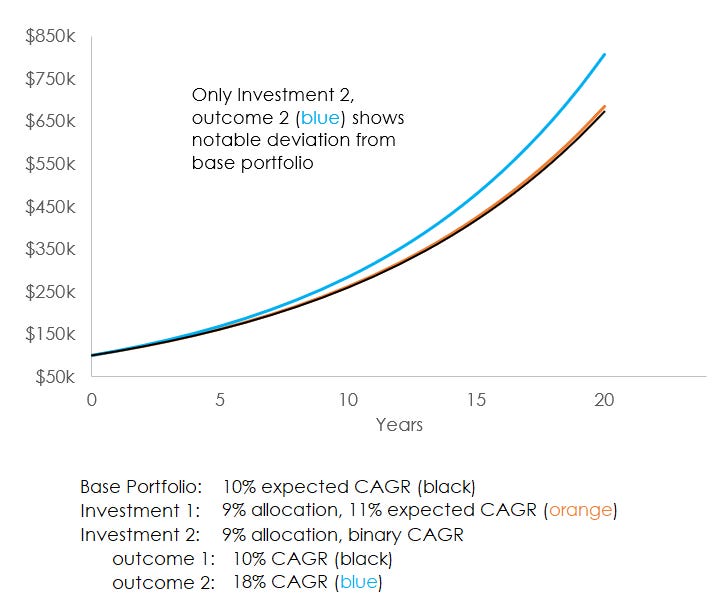

To give a more concrete example, here are two investments:

Investment 1 has an 11% guaranteed return

Investment 2 has a 90% chance of compounding at 10% CAGR, and a 10% chance of compounding at an 18% CAGR

Both investments have an 11% expected return, but Investment 2 offers the possibility of higher returns, which may be more impactful on your overall portfolio. And, you can hold a smaller allocation in Investment 2 and still (potentially) lift portfolio returns.

Holding a 9% allocation to Investment 2 has two potential outcomes:

Investment 2 compounds at 10% CAGR - Total portfolio compounds at 10%.

Investment 2 compounds at 18% CAGR - Total portfolio compounds at 11%.

Alternatively, to capture 11% portfolio returns with Investment 1, you’d need to allocate 100% of your portfolio to it. And if you were to only allocate the same 9% to Investment 1, your expected excess returns would be 10 basis points which falls well short of our 100 basis point cutoff requirement.

Figure 3 illustrates this effect. A small allocation to marginal outperformance won’t move the needle for overall portfolio growth. This highlights the benefits of pursuing asymmetric opportunities, even when expected returns are the same.

The Marginal Position

There’s a couple ways we can think about required excess returns. First, consider that we have a base portfolio (we’ll call “Base”) with expected returns of 10% CAGR. For this exercise, we’ll assume that this “Base” position is already optimally diversified - so adding a new security to it doesn’t offer any new diversification benefits.

Earlier we lay out the case that adding a new position should enable 100 basis points of outperformance - or enough to raise our total portfolio return to 11%.

How should we think about this in terms of adding the next security to our portfolio? If our portfolio of “Base + Security 1” now has an expected return of 11%, it makes sense that adding the next security should improve excess returns 100 basis points above and beyond that, such that “Base + Security 1 + Security 2” would have an expected return of 12%.

In this sense, every position needs to buy it’s way into the portfolio.

But what about “strategy” solutions? What if we consider “Security 1 + Security 2” as a package? Say, purchasing Merck & Pfizer as a pharma “play”, for example. Or say we want to add a factor tilt strategy to our portfolio - purchasing dozens of stocks with low PE ratios, for instance - how should we think about the marginal position then?

In general, it’s reasonable to consider a package of securities as a single position. If I think pharma stocks are cheap on a P/X basis, and want to start a position but don’t have any useful knowledge that increases conviction for any one player, we should be able think of this position holistically. We wouldn’t need our Pfizer position to boost us 100 bp, and then our Merck position to boost us 100 bp above that, and then our Lilly position to boost us 100 bp above even that (for a grand total of 13% portfolio expected returns). We’ll just package those up and consider [Pfizer + Merck + Lilly] as one position, and size with the hope of increasing portfolio returns by 100 bp.

Your next question might be “can I consider a full trading account as a single ‘package’?”.

Yes, but…

Consider a person that has 70% in diversified index funds, and keeps 30% in a separate brokerage account to try and beat the market. Lets also assume that this person wants to own 20 individual stocks in this portfolio; each position makes up 1.5% of their total portfolio.

Referring back to Figure 1, we’d need that account to return 13% CAGR in order to capture 100 bp of portfolio level excess returns. That seems like a manageable feat. But there are reasons to be careful here.

First, consider the scenario provided above with Investment 2. (Investment 2 had an 10% chance of large returns and 90% chance of market returns - with a net expected return of 11%). I made the argument that it can be worthwhile using the the high end range of potential returns to determine your position size. However, owning a basket of similar type bets in your brokerage account would simply result in netting the expected return of 11% for the basket, in total. It’s like going to a roulette table and making a long series of small bets. The end result would have no variance, and you’d leave the table with the expected outcome, which is less money than you started with.

And second, it takes a lot a time to research an idea. Does it make sense to build up a high level of conviction, and then only invest 1.5% of your net worth in it?

In order to consider a full brokerage as one entity, the securities in that basket need to be highly correlated to each other (i.e., a sector bet or a factor bet like I demonstrated above).

Alternatively, if one has high levels of Type I conviction - i.e., having an actual edge - they can kind of do whatever they want, just as long as it doesn’t violate opportunity cost guidelines below.

Opportunity Cost

The lower bound for position sizing should probably be set a level where the resulting outcome is at least at a reasonable hourly wage.

If you’re putting in hundreds of hours into an idea, it doesn’t make sense to then turn around and put $1000 into that investment. If that investment grew at the market rate, you’re implied compensation for that research would essentially come out to less than a fast food worker. Even if it were to become an eventual ten-bagger within a decade, you’re looking at compensation similar to a new-grad.

This also plays into “longevity to resolution”. If you’re going to put hundreds of hours into researching an idea, and proceed to let it compound for a decade or more, that is very different from doing something like day-trading where you might be spending every minute of every day trying to scalp a couple of basis points. The excess returns from day-trading would need to be astronomical to overcome the amount of effort you’re putting into it.

Intangible Returns

There’s a lot of reasons to ignore these guidelines. If you’re early career, you don’t have a lot of money, and any security selection that you make most likely won’t have a large impact on your long term wealth. Most of that will come from savings rates and base investment returns. But there are still good reasons to invest in individual securities (if that interests you).

For one, there is a lot of utility that you gain from learning how markets and investing works. Knowledge compounds. Everything new thing that you learn is built on the collective knowledge you’ve gained before it. Every time you do research, you might learn something new about risk premiums or valuations or how an industry works. This, in turn, will be useful later. Maybe you decide to explore a different company in an industry that you’ve already learned a lot about. Or once you’ve learned how to read a cash flow statement, that will be useful every time you look into a new security. Even if there’s no measurable payoff now, it will certainly be tangible later.

Mistakes are cheap early, and expensive later. You want to make your investing mistakes when you don’t have a lot of money. Buy high, sell low. Day trade (I know you wanna). Buy penny stocks. I’ve done all of these in my early years, and the lessons learned from experience are unmatched. The sooner you get this out of your system, the sooner you’ll become a better investor. You don’t want to wait until you have a lot of money to make these mistakes.

Knowledge transfers. Being able to assess how businesses are valued and how returns are generated helps you with decision making at the portfolio level, even if you’re a strict Boglehead disciple.

Keep a small “cowboy account” to scratch an itch. Trading / investing and staying focused on a tiny fraction can be a source of misdirection, and can help keep you from making rash decisions with your overall portfolio.

Bringing It All Together

Determining the right position sizing for a new asset that you want to add to your portfolio is a balancing act between conviction and expected returns. If you don’t have enough conviction or the expected (or potential) returns aren’t high enough, that security probably hasn’t earned a place in your portfolio.

It’s a high hurdle to clear.

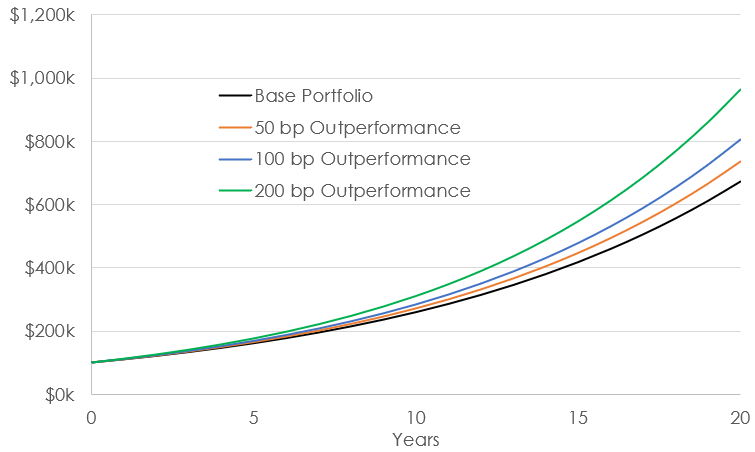

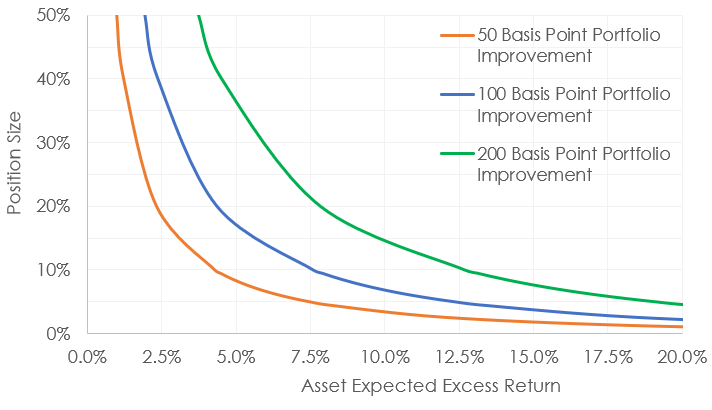

Figure 4 restates Figure 1, but with the axes switched (excess expected return on the x-axis, position size on the y). It shows the 100 basis point threshold that was described above as well as adds the same exercise, but with 50 basis points & 200 basis points as well.

Note that the x-axis is now excess expected return instead of total CAGR (as in Figure 1).

If your base portfolio has expected returns of 10% CAGR, and you find an asset that you believe has an expected return of 15% (500 basis point excess return), you probably need to allocate at least 8% of your portfolio to that asset. This would result in a 50 basis point portfolio performance improvement (orange line).

As explored earlier, you can treat your trading brokerage balance as a single asset, but you’d need to have higher confidence in the expected return profiles at the individual security level.

Portfolio Level Returns

Just a quick note on portfolio returns for the given levels of outperformance. 50, 100, and 200 basis points of annual outperformance might sound like a lot, but it’s really not.

After ten years, that amounts to 5%, 10%, and 20% cumulative outperformance, respectively, compared to the base portfolio.

After twenty years, cumulative outperformance grows to 10%, 20%, and 43%, respectively.

I would consider 200 bp of outperformance to be the cutoff for being a truly worthwhile pursuit. But that’s also prohibitively hard to achieve without either dedicating a very large allocation to performance chasing or pursuing very high return opportunities - as described in Figure 4 - which, on the surface, sounds like a very risky endeavor.

Personal Revelations

The main impetus for writing this post was due to my own observations on position sizing and impact on portfolio growth.

I’m primarily a Boglehead investor, keeping 90% or more of my portfolio in broadly diversified index funds. This leaves about 10% of my net worth to play around with in individual securities. I keep that 10% in just a regular brokerage account.

In that account, I have historically tried to maintain anywhere between 10 & 20 securities. The implication here is that each individual position ends up being around 0.5% of my net worth. I believe this works out to be smaller than my exposure to the top companies in my S&P 500 index holding.

As an illustration, I purchased Spotify in 2023 and subsequently earned a 300% return on it in the 2.5 years that I held it (about a 74% annualized return). It was a pretty small position, and that particular holding accounted for 0.32% of my net worth at the time of purchase. Which means, even capturing a 4-bagger in 2 years, it accounted for less than 50 basis points per year of total portfolio performance (much less in terms of driving excess growth). That’s a lot of research and general effort to not really move the needle in the grand scheme.

I used to hold the belief that my “strategy” should drive outperformance rather than rely on a few anchor positions to determine success or failure of my portfolio. While this is a fine way of thinking, I’ve also noticed that there is an inverse relationship between the number of individual securities that I hold and the depth of research that I can do on each one. Which then equates to inherently larger error bars in my assessment of fair value. And, it also means that I have less conviction in each individual pick (I have on more than one occasion been shaken out of a position due to price action - which is a surefire sign of lack of confidence in my value assessment).

Going forward, my plan is to hold position sizes of at least 2% of my overall net worth in any individual security, and target securities that I believe will outperform by at least 500 basis points (roughly 12% to 15% absolute returns depending on the expectations for market & portfolio returns). If I can’t find any, I’d prefer to stick with passive funds or even dry powder.

Even these numbers fall short of the guidelines laid out in Figures 1 & 4, but I’m also considering two things, here. First, my positions currently have more binary distributions; I can use “potential returns” to size those holdings. Also, I’m considering downside protection as well (a tangible benefit not covered in this article). 2% position size “feels” about right for protecting against downside scenarios - I can see a position drop 50% with only minor impact on overall wealth.

This now means that my individual brokerage will shrink to between 2 & 5 positions. This does a couple things for me:

Promotes deeper research into each holding and hopefully higher conviction.

Allows for higher conviction picks to anchor my portfolio.

I’ve held Quantumscape through a 50%+ drawdown and never waivered (not that I have Type I conviction in terms of confidence that they will surely succeed, but rather I felt that I have a good enough handle on the business to properly assess it). And, I never felt like I was bag-holding.

Meanwhile, I owned Toast for a few weeks and was shaken out after a 10% dip because I know almost nothing about the company (although that’s one that I want to take another look at).

Improve my exposure to luck. Holding a 2% position in something that becomes a 10-bagger would obviously be very meaningful. And it’s better to take a few shots on things like this because the more you own, the more likely you are to average out your returns. If you sit down at a roulette table, it’s better to bet your entire stack on one roll rather than spread it out over many. If we consider 1000 parallel universes, 26 versions of you would become rich in the former scenario (betting it all at once); 974 versions of you would lose the bet. In the latter scenario, every single 1000 versions of you will walk out of the casino with less money. If that’s the case, why even play?

Likewise, this all applies to general portfolio construction as well. If you’re bullish on India, don’t allocate just 1% to your Indian fund of choice. Don’t allocate just 1% to bonds…or EM…or International. There’s virtually no difference to performance or volatility between a 1% allocation and a 0% one.

And, in general, be mindful of what makes it into your portfolio, and make sure that every position has earned its place.

This is for demonstration purposes only. Markets may or may not reach these levels of returns, nor may they currently have this level of expectations. Yes, I know that Vanguard projects 4% returns for U.S. stocks. Again, this is just a demonstration.